These stories are of people who have been the firsts -- either out of will or circumstance. To be first is to be brave, to encounter challenges unlike those of others in the same environment and, in that regard, to be lonely as well. We want to recognize these people for carving out paths in history for all those who came afterwards, for showing us the possibility.

anthony oyewoleIn 1964, Nigerian student Anthony Oyewole transferred to a newly desegregated Duke University as an undergraduate junior. He graduated the following year, thus becoming the first Black person to earn a Duke degree.

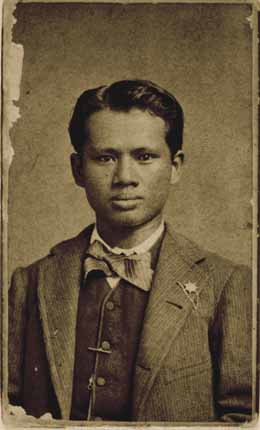

charles j. "Charlie" soongCharlie Soong, born in the Hainan Province of China, was the first international student at Trinity College. In 1881, he enrolled in a special course of study to become a Methodist missionary, and his tuition was paid for by Braxton Craven and Julian Carr.

duke's first black graduate school studentsDespite efforts by the Divinity School student body to petition for an end to segregation at Duke beginning in 1948, it was not until 1961 that Ruben Lee Speakes and Walter Thaniel Johnson Jr. enrolled at the Divinity School as its first African American students. David Robinson, who enrolled at the Law School the same year, later became North Carolina's first Black assistant district attorney.

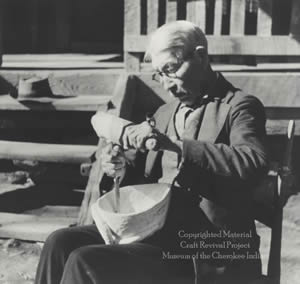

duke's first native american students Will West Long at home, carving a dance mask. Courtesy Museum of the Cherokee Indian and Western Carolina University Will West Long at home, carving a dance mask. Courtesy Museum of the Cherokee Indian and Western Carolina University

. In 1879, the US government began a program designed to forcibly assimilate Indigenous peoples by taking their children to distant boarding schools. The first of these schools was Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. According to the Carlisle Indian School Project, administrators forced students to “cut their hair, change their names, stop speaking their Native languages, convert to Christianity, and endure harsh discipline including corporal punishment and solitary confinement. This approach was ultimately used by hundreds of other Native American boarding schools, some operated by the government and many more operated by churches.”

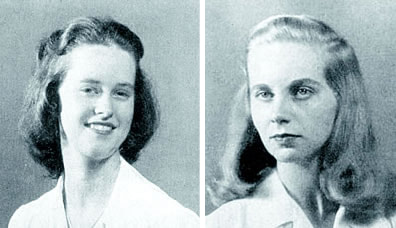

The philosophy of these schools was, in the words of their founder, to “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.”[1] One of those schools operated at Trinity College from 1880-1881, then again from 1882-1885. At least 20 Eastern Band of the Cherokee boys attended. Originally sponsored by then-university president Braxton Craven, the students came with a government stipend as well as a requirement that they do farm chores. This was a common requirement at the time for any poor student, who offset the cost of their education through work. Like Carlisle, Trinity's school was eventually dubbed an “Industrial” school.[2] One of the students was Will West Long. His Cherokee name was Wili Westi. Part of a small group of Cherokee who fled the forced removal known as the “Trail of Tears,” Long was born and raised in Big Cove, in what was known as the Qualla Boundary. He arrived on campus in 1882 when he was 12 or 13. He and most of the other Cherokee spoke and wrote no English. The Cherokee were kept separate from the White students. Records are thin but the Cherokee likely suffered from racism, cultural violence, and hunger, since they couldn't wear their own clothes, sleep in familiar beds, speak Cherokee, worship, or eat traditional food. Records show that Long experienced profound isolation and exploitation. He escaped and tried to return home twice but was returned to campus.[3] Long later chose to study at Hampton University, a historically Black college. He became a renowned historian of Cherokee customs and lifeways and a key source of information for ethnologists, anthropologists, historians, and archeologists who visited the Cherokee during his lifetime.[4] Some of the records from Duke's University Archives are accessible here and here. [1] K. Tsianina Lomawaima and Jeffrey Ostler. “Reconsidering Richard Henry Pratt: Cultural Genocide and Native Liberation in an Era of Racial Oppression.” Journal of American Indian Education, 57, no. 1 (2018): 79–100. https://doi.org/10.5749/jamerindieduc.57.1.0079. [2] Chaffin, by Nora Campbell. Trinity College, 1839-1892: The Beginnings of Duke University. Duke University Publications. Durham, N.C. 1950. https://find.library.duke.edu/catalog/DUKE000257684. [3] Ingram, Jill Elizabeth. “Man in the Middle: The Boarding School Education of Will West Long.” Masters Thesis, Western Carolina University, 2008. [4] Fariello, Anna. “Cherokee Traditions | People | Will West Long (1870 - 1947).” Accessed December 10, 2021. https://www.wcu.edu/library/digitalcollections/cherokeetraditions/people/Carvers_WillWestLong.html. duke's first women engineersMarie Foote Reel enrolled in the Women's College in 1943, but later transferred to the College of Engineering despite opposition from administrators, faculty, and staff. She graduated magna cum laude. Her contemporary, Muriel Theodorsen Williams faced similar obstacles as a woman in a traditionally man-dominated field.

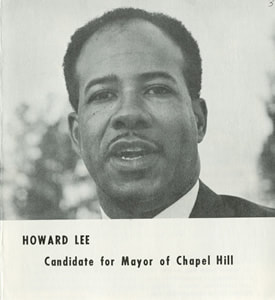

howard leeWhen Howard Lee was elected mayor of Chapel Hill in 1969, he became the city's first African American mayor, as well as the first African American mayor elected to any predominantly white city in the South. Prior to his career in public service, Lee served as Duke's Director of Employee Relations for Non-Academic Employees.

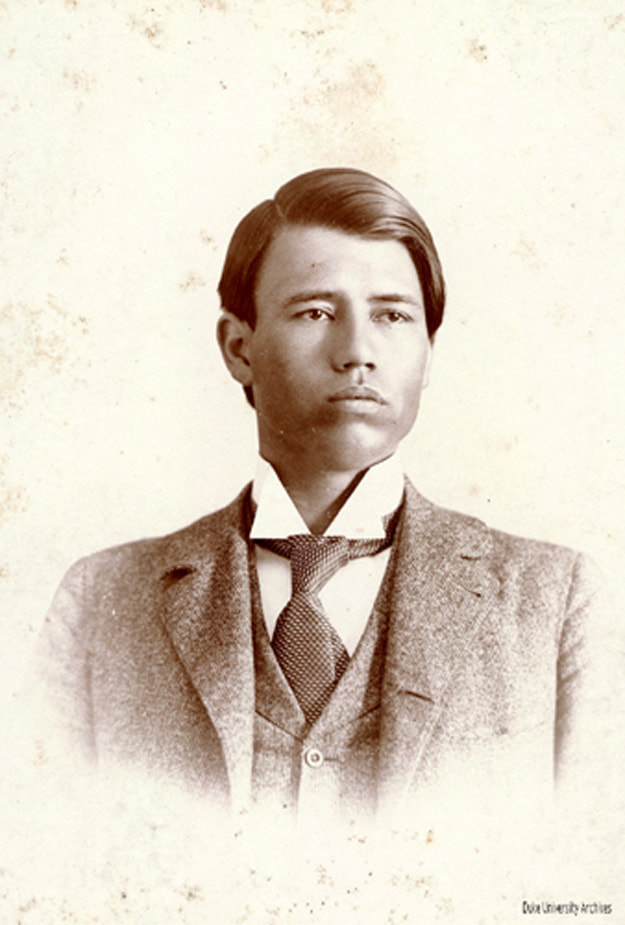

joseph S. maytubbyIn 1896, Joseph Maytubby of the Chickasaw nation in Oklahoma, became the first Native American student to graduate from Trinity College. He was later elected the first mayor of Tishomingo, Oklahoma.

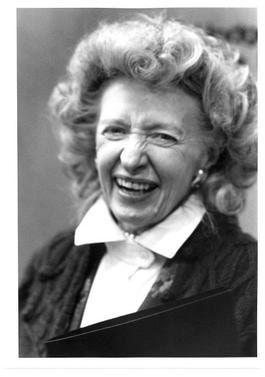

mary duke biddle trent semansSemans, the great granddaughter of Washington Duke, became one of the first women elected to the Durham City Council, after running on a platform to ensure African American voting rights. She also served as the first woman chair of the Duke Endowment from 1982 to 2001.

|

the bassett affairTrinity College professor John S. Bassett published an article praising Black educator Booker T. Washington in 1903. White supremacist leaders opposed this idea and called for his resignation. The Board of Trustees ultimately voted to keep Bassett as a faculty member, thus showing their commitment to freedom of speech as a hallmark of the institution.

brenda armstrongDr. Brenda Armstrong was among the first African Americans to attend Duke University as an undergraduate student, and later became the second Black woman in the nation to become a board-certified pediatric cardiologist. In addition to her professional accomplishments, Armstrong has a rich legacy of activism, helping to found the Afro-American Society in 1967 and organizing students during the Allen Building Takeover in 1969. She currently serves as the Senior Associate Dean of Student Diversity, Recruitment, and Retention at the Duke School of Medicine.

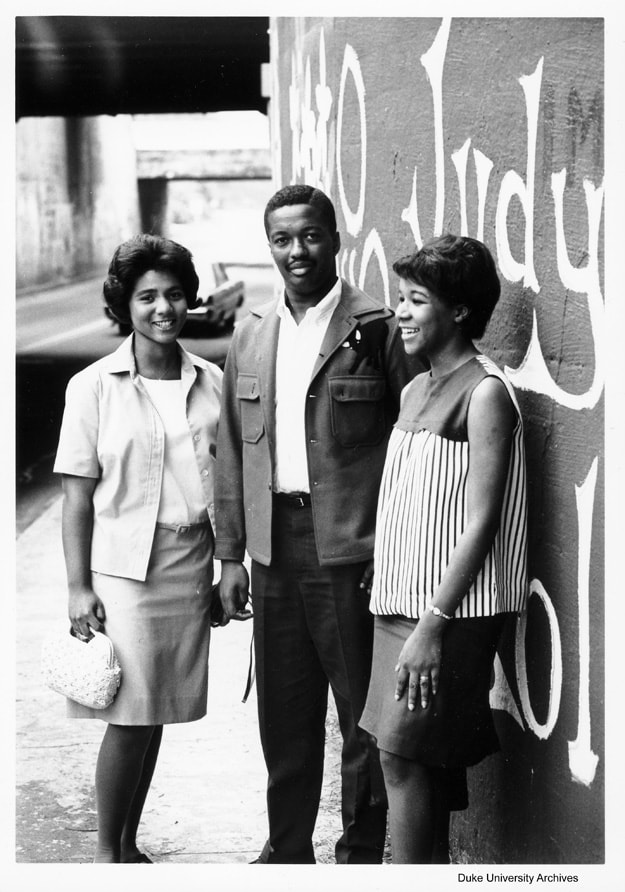

duke's first black undergraduate studentsIn the fall of 1963, Wilhemina Reuben-Cooke, Mary Mitchell Harris, Gene Kendall, Cassandra Smith Ru, and Nathaniel White Jr. became the first Black undergradute students to enroll at Duke. The University was among the last schools in the South to desegregate.

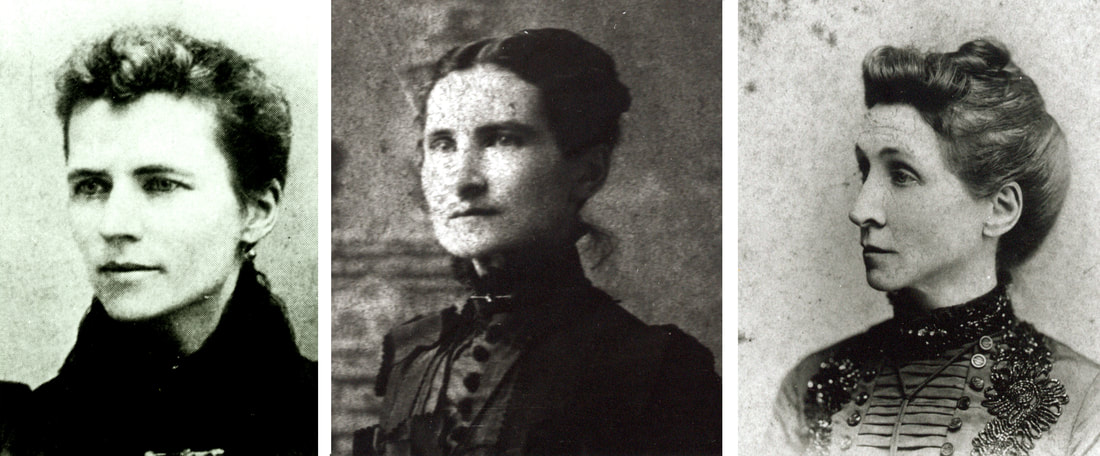

the giles sistersFifty-two years before the Women's College was founded, in 1878, Mary, Persis, and Theresa Giles became the first women awarded degrees by Trinity College. Since the College was an all-male school, the sisters paid tuition and attended private classes but were never fully enrolled. The Board of Trustees voted to grant them degrees upon graduation.

ida s. owensIn 1967, Ida Stephens Owens became the first Black woman to receive a PhD from Duke University, in Biochemistry and Physiology. She is recognized as an expert in the field of drug detoxifying enzymes. In 2013, she became the first recipient of the Graduate School Distinguished Alumni Award.

katherine E. gilbertDuke University appointed Katherine Everett Gilbert to be professor of philosophy in 1930, thus making her the University's first full woman professor. Gilbert-Addoms Residence Hall on East Campus is named for her and her contributions.

reginaldo"reggie" howardReggie Howard was elected president of the Associated Students of Duke University in 1976, becoming the first African American to hold that position. Following his death, the University started a merit scholarship in his name to support exemplary students of African descent.

samuel dubois cookPolitical scientist, educator, and civil rights activist, Samuel Dubois Cook became the first tenured Black professor at Duke University in 1966. He was also the first Black person in the nation to hold a regular faculty appointment at any predominantly white college. During his tenure, Cook helped form a community for Black students and supported campus movements, such as the Silent Vigil of 1968.

|

DO YOU KNOW A STORY WE DON'T?

Please share with us, so that we can continue to grow this database.