Led by a faculty member, a graduate student and ten undergraduates, we explored human rights, memory studies and Duke’s history and campus over the course of two semesters. We counted on support from Dr. Alison Adcock, Associate Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Duke, for her work on how people retain information from exhibits; Tim Stallman, a cartographer; and Hannah Jacobs, in Digital Humanities. We asked how, why and where people around the world use the past for contemporary meaning; and how people absorb and retain information and meaning. We took Duke as a laboratory for how communities remember, embody and tell their stories — or leave some stories, including difficult or controversial ones, unrecorded in official accounts or physical sites.

For our project, we took as inspiration other universities’ efforts to understand and acknowledge their histories. To paraphrase the Brown University Slavery and Justice Committee, our report is a call and invitation to our community to engage in intentional reflection and fresh discovery without provoking paralysis or shame. We hope this report contributes to a deeper engagement with Duke’s history and concrete action on how that history is memorialized. As part of our project, we are proposing new sites, initiatives and interpretive plans to enrich and broaden an on-going discussion.

Our team was interdisciplinary, with a journalist and writer, a cartographer, a cultural anthropologist, a neuroscientist, a digital humanities specialist and university archivists. We also brought in invited speakers to explore processes at other universities, among them Brown, Winston-Salem State, Yale and the University of Illinois-Chicago. The report was written by Robin Kirk, with assistance from the students and the University Archives, among many others.

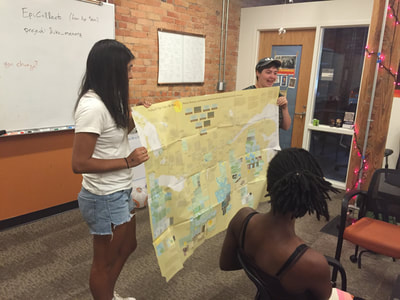

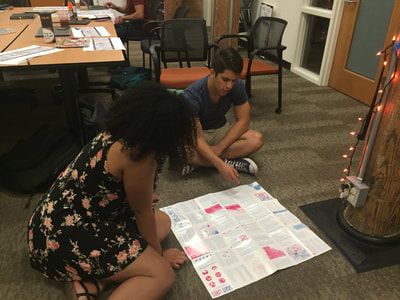

Students started the Duke-specific phase of our project by digitally mapping the campus, to show where and how Duke physically tells its story. To help make our case that important stories have gone undervalued or untold, we assembled a Story Bank drawn from the University Archives to show some of the key figures and moments that should be recognized at Duke. The Story Bank reflects the views of the students and their desire, more focused with each week of the project, to lift up forebears and honor the pathways they carved and that brought these students to Duke. Among those featured in the Story Bank are "firsts," including women, African Americans and Native Americans; and examples of principled leadership, including among the students, faculty and staff who led the Silent Vigil, Student Action with Farmworkers and the Anti-Sweat Shop campaign. We hope the Story Bank is a resource as the Duke community moves forward.

Students also designed site proposals, based on parts of history they felt needed to be commemorated or emphasized. New sites would help reshape the campus into a place that more accurately honors the rich contributions made by many people, inspire current and future students to see themselves in this space and encourage all to strive to uphold our shared values.

Many members of our community feel the weight of sites that celebrate white supremacy, violence and exclusion – and the accompanying weight of erasure and absence – every time they step on campus. The fact that others – including many white people – do not feel or even acknowledge that weight is not evidence that it doesn’t exist, but rather a powerful and shocking proof that sites and absences can corrode the perceptions of even the most well-meaning ally. To adequately address the past and move toward justice and equality, we must speak truth in both word, deed and brick and mortar. As President Price noted, we must to continue to build — not just metaphorically, but actually — a university that “lives up to our values, recognizing our past even as we strive to be better.”

For our project, we took as inspiration other universities’ efforts to understand and acknowledge their histories. To paraphrase the Brown University Slavery and Justice Committee, our report is a call and invitation to our community to engage in intentional reflection and fresh discovery without provoking paralysis or shame. We hope this report contributes to a deeper engagement with Duke’s history and concrete action on how that history is memorialized. As part of our project, we are proposing new sites, initiatives and interpretive plans to enrich and broaden an on-going discussion.

Our team was interdisciplinary, with a journalist and writer, a cartographer, a cultural anthropologist, a neuroscientist, a digital humanities specialist and university archivists. We also brought in invited speakers to explore processes at other universities, among them Brown, Winston-Salem State, Yale and the University of Illinois-Chicago. The report was written by Robin Kirk, with assistance from the students and the University Archives, among many others.

Students started the Duke-specific phase of our project by digitally mapping the campus, to show where and how Duke physically tells its story. To help make our case that important stories have gone undervalued or untold, we assembled a Story Bank drawn from the University Archives to show some of the key figures and moments that should be recognized at Duke. The Story Bank reflects the views of the students and their desire, more focused with each week of the project, to lift up forebears and honor the pathways they carved and that brought these students to Duke. Among those featured in the Story Bank are "firsts," including women, African Americans and Native Americans; and examples of principled leadership, including among the students, faculty and staff who led the Silent Vigil, Student Action with Farmworkers and the Anti-Sweat Shop campaign. We hope the Story Bank is a resource as the Duke community moves forward.

Students also designed site proposals, based on parts of history they felt needed to be commemorated or emphasized. New sites would help reshape the campus into a place that more accurately honors the rich contributions made by many people, inspire current and future students to see themselves in this space and encourage all to strive to uphold our shared values.

Many members of our community feel the weight of sites that celebrate white supremacy, violence and exclusion – and the accompanying weight of erasure and absence – every time they step on campus. The fact that others – including many white people – do not feel or even acknowledge that weight is not evidence that it doesn’t exist, but rather a powerful and shocking proof that sites and absences can corrode the perceptions of even the most well-meaning ally. To adequately address the past and move toward justice and equality, we must speak truth in both word, deed and brick and mortar. As President Price noted, we must to continue to build — not just metaphorically, but actually — a university that “lives up to our values, recognizing our past even as we strive to be better.”