April 19, 2018, Durham, NC

A Duke student research team today released a report that documents the university’s ties to slavery, white supremacy and discrimination and calls on the school to change how history is memorialized on campus.

“Activating History for Justice at Duke” joins efforts at schools like Brown, Georgetown, Yale and the University of North Carolina to revisit their pasts. Over the past eighteen months, students researched in the University Archives, mapped memorials on campus and designed their own sites.

Students discovered that of the 327 sites they mapped, 53 per cent honor white men. Among them are slave owners and white supremacists like Duke’s longest-serving president, Braxton Craven. Duke’s History Department is housed in the Carr Building, named for industrialist Julian S. Carr. Along with donating the land where East Campus sits, Carr was a virulent white supremacist who also supported the 1898 Wilmington coup d’ etat against black leadership, considered the only violent government takeover in US history.

Helen Yu (Trinity 2018), a member of the research team, identifies as an immigrant and a woman of color. “Not being a part of official history has become a norm for me. This project puts into writing the stories of people just like my peers and me who fostered vibrant communities and stood up justice, but were never honored. I want administrators to start paying attention to the contributions that everyone makes to the university — not just the contributions of wealthy white men.”

Students assembled a Story Bank drawn from the University Archives to show key figures and moments that should be recognized at Duke. Among them are George Wall, a former slave who was among the only employees of Trinity College, Duke’s precursor, to move from Randolph County to Durham; and Lillian Griggs, a pioneering librarian who created the first bookmobile.

Jair Oballe (Trinity 2019), a member of the research team, observed that Duke University hosts internationally renowned guests, but once events conclude, “the doors close and conversation ends. Why is our university so unwilling to construct permanent memorials that celebrate local and international activism on our campus? We can showcase a campus that commits itself to dialogue not just about our oppressive past, but a vision for a just future.”

Students proposed honoring activists who pushed to make the campus a place that welcomed a more diverse student body. Among them they highlighted Oliver Harvey, a long-time Duke employee who led the effort to unionize Duke workers. The report includes eight proposed sites designed by students that honor students of color, women and values like free speech.

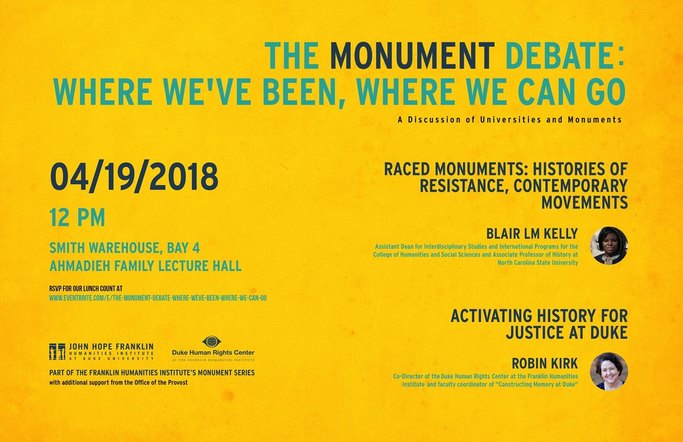

Robin Kirk, a co-director at the Duke Human Rights Center @ the Franklin Humanities Institute, directed the project. “Once they began digging, students realized that the campus itself is a powerful teaching tool, and needs more sites to forbears like the black students who integrated the campus and the staff who contribute so much to the university’s life.”

Students also created a coloring book of Duke sites and figures and a video explaining their call to diversity campus sites. The report is available at www.activatinghistoryatduke.com.

In addition to Bass Connections, students worked with the Duke Human Rights Center @ the Franklin Humanities Institute, the Duke University Archives, Story Lab, the Pauli Murray Project and the Wired! Lab.

“Activating History for Justice at Duke” joins efforts at schools like Brown, Georgetown, Yale and the University of North Carolina to revisit their pasts. Over the past eighteen months, students researched in the University Archives, mapped memorials on campus and designed their own sites.

Students discovered that of the 327 sites they mapped, 53 per cent honor white men. Among them are slave owners and white supremacists like Duke’s longest-serving president, Braxton Craven. Duke’s History Department is housed in the Carr Building, named for industrialist Julian S. Carr. Along with donating the land where East Campus sits, Carr was a virulent white supremacist who also supported the 1898 Wilmington coup d’ etat against black leadership, considered the only violent government takeover in US history.

Helen Yu (Trinity 2018), a member of the research team, identifies as an immigrant and a woman of color. “Not being a part of official history has become a norm for me. This project puts into writing the stories of people just like my peers and me who fostered vibrant communities and stood up justice, but were never honored. I want administrators to start paying attention to the contributions that everyone makes to the university — not just the contributions of wealthy white men.”

Students assembled a Story Bank drawn from the University Archives to show key figures and moments that should be recognized at Duke. Among them are George Wall, a former slave who was among the only employees of Trinity College, Duke’s precursor, to move from Randolph County to Durham; and Lillian Griggs, a pioneering librarian who created the first bookmobile.

Jair Oballe (Trinity 2019), a member of the research team, observed that Duke University hosts internationally renowned guests, but once events conclude, “the doors close and conversation ends. Why is our university so unwilling to construct permanent memorials that celebrate local and international activism on our campus? We can showcase a campus that commits itself to dialogue not just about our oppressive past, but a vision for a just future.”

Students proposed honoring activists who pushed to make the campus a place that welcomed a more diverse student body. Among them they highlighted Oliver Harvey, a long-time Duke employee who led the effort to unionize Duke workers. The report includes eight proposed sites designed by students that honor students of color, women and values like free speech.

Robin Kirk, a co-director at the Duke Human Rights Center @ the Franklin Humanities Institute, directed the project. “Once they began digging, students realized that the campus itself is a powerful teaching tool, and needs more sites to forbears like the black students who integrated the campus and the staff who contribute so much to the university’s life.”

Students also created a coloring book of Duke sites and figures and a video explaining their call to diversity campus sites. The report is available at www.activatinghistoryatduke.com.

In addition to Bass Connections, students worked with the Duke Human Rights Center @ the Franklin Humanities Institute, the Duke University Archives, Story Lab, the Pauli Murray Project and the Wired! Lab.