True emancipation lies in the acceptance of the whole past, in deriving strength from all my roots, in facing up to the degradation as well as the dignity of my ancestors.

Pauli murray, proud shoes

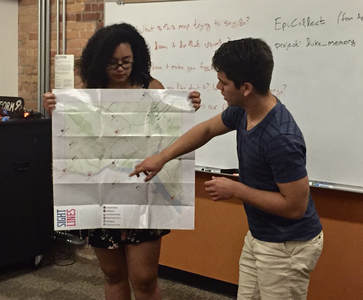

Two students, Catherine and Jair, interpret cartography of resistance

Two students, Catherine and Jair, interpret cartography of resistance

This report began as a Bass Connections project, “Constructing Memory at Duke and in Durham: using memory studies to create social justice.” This followed “Memory Bandits,” a series of courses examining the role of memory and archives in social justice offered in conjunction with Cultural Anthropology and Duke’s Human Rights Archives. The name comes from Verne Harris, the archivist for the papers of Nelson Mandela and now director of the Memory Programme at the Nelson Mandela Foundation's Centre of Memory and Dialogue. Harris sees himself as a “memory bandit,” a Robin Hood of the archiving world who “redistributes the rich seam of memory in the service of the oppressed.”

Led by a faculty member, a graduate student and ten undergraduates, we explored human rights, memory studies and Duke’s history and campus over the course of two semesters. We asked how, why and where people around the world use the past for contemporary meaning; and how people absorb and retain information and meaning. We took Duke as a laboratory for how communities remember, embody and tell their stories — or leave some stories, including difficult or controversial ones, unrecorded in official accounts or physical sites.

Led by a faculty member, a graduate student and ten undergraduates, we explored human rights, memory studies and Duke’s history and campus over the course of two semesters. We asked how, why and where people around the world use the past for contemporary meaning; and how people absorb and retain information and meaning. We took Duke as a laboratory for how communities remember, embody and tell their stories — or leave some stories, including difficult or controversial ones, unrecorded in official accounts or physical sites.